| Prev |

(my father, born 27th July 1935, died 12th August 2010)

Neil Huggett: I want to present these pieces written by my father, Raymond Huggett, as they do give some interesting insights into aspects of 'everyday life' in Australia, from many years ago (1938 - around 1954). Obviously, I am biased in my appreciation of these stories. |

Page menu:

| Foreword My earliest memories, like those of everyone else I suppose, are somewhat fragmented. Some of the images have been reinforced by photographs and others recounted in my hearing by my mother to sundry friends and relations. So it would be fair to say that various script details of the different scenes of childhood are second hand or recently confirmed with reference to old photo albums. I cannot, alas, call on my dear Mother or Father for any assistance. Nonetheless many, if not most of the salient aspects remain indelibly etched in my mind. Not surprisingly, the scenes which stand out in the memory were certainly the more dramatic ones. Those close encounters with danger and life threatening situations were certainly among the most prominent. Raymond Huggett, Sydney, March 1995. Back to page menu | Back to writing menu |

| Little Boy Lost In the latter half of 1938 we were living at Brisbane Avenue, Five Dock (one of the suburbs in Sydney, and adjacent to Parramatta River). Dad was working at the Berger Paints factory at Rhodes which is on the same side of the Parramatta River but about 5 miles further west as the crow flies. We had been living there since the year before and I would have been about three and a half, which explains why I don’t remember too much about it. Apparently, I used to like answering the ‘phone and Mum often recited in a little voice the way I used to say “D’moyne Seven Five ‘lo” to the manual exchange operator — for Drummoyne 750. We had a small brick house not very far from the river on the other side of the unsealed Henley Marine Drive. It was possible at low tide, by skirting around the rocks and the muddy patches, to walk along the foreshore. It was a very pleasant spot. We were lucky that we were able to use a little sandy beach and although not nearly in the class of Bondi, Mum used to help me build sand castles and allow me to paddle in the shallow water as long as she or Dad was there to watch me. I had a small blue Cyclops car which I pedalled and pushed along the cement paths around the house and that’s where Mum thought I was one morning about 9 o’clock when she was on the ‘phone, probably talking to Grandma. |

She started calling out my name as she raced across to the beach. When she arrived at the car her heart sank as she could plainly see the wheel tracks in the sand where I had pedalled the car until I couldn’t go any further and beyond that were the footprints of my sandals going right down into the water! As she looked desperately around, she could see some workers on a construction site further along Henley Marine Drive so she headed straight to them. It wasn’t long before they all downed tools and came back to help. A couple of the men went up towards the Iron Cove Bridge and another two started working their way round the southern Iron Cove shoreline. The foreman came back to the house and organised a full search of the house itself — inside, outside and underneath. By the time this was completed the other workers were back from their fruitless search along the shore. It was time to bring in the Drummoyne police. By 10 o’clock they were on the scene, Dad was home from work and Mum was frantic. They told the police that I’d never wandered off before and I never played down near the water unless I was supervised. Dad went off in his car to the local shopping centre to ask the shopkeepers if anyone had seen me. The police organised a house to house search up and down the local streets and patrols around the Five Dock and Drummoyne area, but the Sergeant in charge was worried about the tracks leading into the water. By now they were covered by the rising tide. The hours passed. All the obvious places had been checked and rechecked and it seemed that the only place left was the river itself so grappling hooks were brought in for the police to start dragging the edge of the river. They started just where the blue car had been. Dad took Mum into the house to try to comfort her. It was almost 4 o’clock in the afternoon when the ‘phone rang. It was the Ryde police and they had found a boy fitting the description of the one who was missing. “He said his name was Raymond and he was looking for Daddy” said the desk Sergeant. “He was found in the Ryde pub.” Twenty minutes later the police car arrived and I was in the back sitting between two constables and grinning from ear to ear. Everyone gathered around and a huge policeman lifted me out and asked Mum, “Is this your little boy?” “Yes it is. Give him to me. I’m going to take him inside and give him a dashed good hiding”, said Mum. I stopped grinning. “Well in that case you can’t have him”, said the big cop, holding on to me. “I’ll only let you have him back if you promise not to give him a hiding. “All right”, said Mum, “I promise, but only if he promises never to run away again.” “You won’t run away again, will you Raymond?” he said, looking right into my eyes.” “No, I won’t run away ever again” I vowed. And I never did. The exact route of my extraordinary journey remains a mystery. The puzzling thing to me looking back at all this, is that in broad daylight, as a boy of three and a half, I had certainly walked alongside and across some of Sydney’s busiest roads — most likely Lyons Road, Concord Road, and Victoria Road, for a distance of nearly 10 miles (16 kilometres) and apparently no one had tried to stop me or report me to the police in case I was missing. Indeed I had probably walked straight past the Ryde Police Station. The Ryde Hotel where the publican found me “looking for Daddy” was on the corner of Victoria Road and Ryedale Road and was later pulled down around the time the railway station was renamed “West Ryde”. The old Gladesville Bridge which I could possibly have crossed carried tram tracks as well as a roadway and footpath. It was also pulled down after the completion of the present single arched concrete bridge — the largest of its type in the world. It was opened by the Queen in 1953. It was more likely though, that I had found my way to Lyons Road, Lyons Road West and somehow up to Concord Road. I would then have walked along Concord Road, missed the turnoff to Berger’s, and carried on over the Ryde Bridge to Victoria Road and eventually to Ryedale Road.

Back to page menu | Back to writing menu |

| My First Train Set The occasion of a young boy receiving his first train set is normally a very exciting one, filled with pleasure and wonderment. It usually signifies a birthday or Christmas present and becomes a moment to treasure and remember for many years. Even in more modern times with the proliferation of toys of all kinds there is still something very special about a train set. But for me in 1939 there was no excitement, pleasure or wonderment. It wasn’t my birthday and Christmas was a long, long time away. I was in the Children’s Hospital at Camperdown and my life was in the balance. I had diphtheria. No one knows for sure where I picked up the germ as there were no other cases reported from the school at North Strathfield. Earlier in the year I had been involved in floods at my Uncle Bert’s rice farm at Murrami near Leeton when the Murrumbidgee River broke its banks. Maybe I picked up the germ there. I still remember the swirling muddy waters as far as the eye could see in all directions with Uncle Bert’s house, a few trees and some fence posts standing out as the only landmarks. We all had to get away on a raft made from planks tied to 44 gallon drums. Mum and Dad came in to see me every day but I was in a quarantine ward on my own and they were only able to just look at me and wave from the other side of a glass partition. Most of the time I was too ill to wave back and sometimes I didn’t even know when they were there. I remember Mum crying a lot and Dad trying to comfort her. Each day was the same. My throat was swollen and it was hard to breathe. Then one day there was a change. They wheeled in another bed with a boy about seven or eight and positioned it alongside mine. I’ve forgotten his name but he had red hair. I didn’t know at first but he was very ill with the measles. Apparently I had not been eating, drinking or showing interest in anything at all and the doctors were worried that there had been no signs of any improvement so they decided some company might be good for me. But it still didn’t make any difference. That’s when Dad decided to get the train set. It was clockwork of course — a Hornby with a wind up engine, tender, two carriages and an oval track, all in a cardboard box. A nurse had to bring it in to me. But I just lay there too sick to care and Mum and Dad went slowly away. Later that night they received a fateful ‘phone call. “It’s the hospital here, you had better come down straight away. Your little boy has contracted measles and is running a very high fever. He’s not expected to last the night.” But a miracle happened and by morning the crisis had passed. The measles had somehow saved me and it wasn’t too long before a very relieved Mum and Dad were allowed in to see me. I was sitting up. “Look at all the red spots on me Mum”, I said, opening my pyjama top. Then I looked at the box on top of the cabinet beside the bed. “Dad, could you please set up the train set?” Back to page menu | Back to writing menu |

| Near Tragedy At Tudibaring

It was holiday season. We were all invited by friends of Dad to spend a few days at Tudibaring Beach on the Central Coast. These days the area is better known as Copacabana and is well established with many facilities, a Surf Lifesaving Club, and some fine homes, but in early 1940 there were just a few small holiday homes and more than enough beach for everyone. I don’t remember the names of the people with whom we stayed but I do recall they had a black dog and no children. “Blackie” was very friendly and loved playing on the beach, so Joan and I soon established a good working relationship with him. On this particular day, Dad and his friend had gone off together to sample some of the fishing spots leaving the wives to sit on the beach and soak up some sunshine and perhaps have a swim and play with us. It was a fairly flat surf and ideal for a boy of four and his two year old sister. Joan and I each had a new bucket and spade which we quickly put to good use building sand castles with moats all around which would fill with water from the occasional larger wave. The tide must have been coming in because one wave washed our sandcastle completely away and in the general confusion one of the wooden spades was washed away as well. As we looked around for it we could see it floating on the top and when the next wave arrived it was brought very conveniently inshore where we could easily grab it. Suddenly we had a new game, and soon we had both spades riding the gentle surf in and out. We were having a great time splashing in the shallow water, dodging the waves and picking up the spades. “Blackie” was having a great time too, and was doing his best to grab the spades before we could. Meanwhile our “minders” had apparently not noticed that we had been moving further and further along the beach away from the area that they had selected. There were, of course, no flags to keep between, and no lifesavers, as we virtually had the beach to ourselves. Joan was at a disadvantage in that she was much smaller than I was, so the water which was coming up to my knees was coming nearly up to her waist. This didn’t seem to worry her though as she loved the water and had no great fear of it. When the spade floated out a little further and I hesitated, she moved confidently after it, but as she reached out to grab it — she suddenly disappeared! I started involuntarily towards her but I realised the water was too deep. I would have to get Mum. I turned around and started yelling and instantly “Blackie” started barking. The louder I yelled, the louder he barked. Mum couldn’t hear me for the noise of the surf, but she heard “Blackie”. Mum had been a very fast runner winning many events in an athletics club before she was married, and she wasn’t about to lose this trophy. I maintain it was just as well I hadn’t moved from where Joan had gone under because Mum raced out past me splashing water in all directions and dived straight in almost on top of Joan who Mum later described was lying face up on the bottom, eyes open and swallowing mouthfuls of seawater — just like a fish! Fortunately Joan responded to Mum’s lifesaving treatment that was administered and quickly recovered. A tragedy was averted but I finished up with a hiding — because I shouldn’t have stayed there yelling. “You should have come for me”, Mum said. “What if I hadn’t heard the dog?” Back to page menu | Back to writing menu |

The Air Raid Shelter |

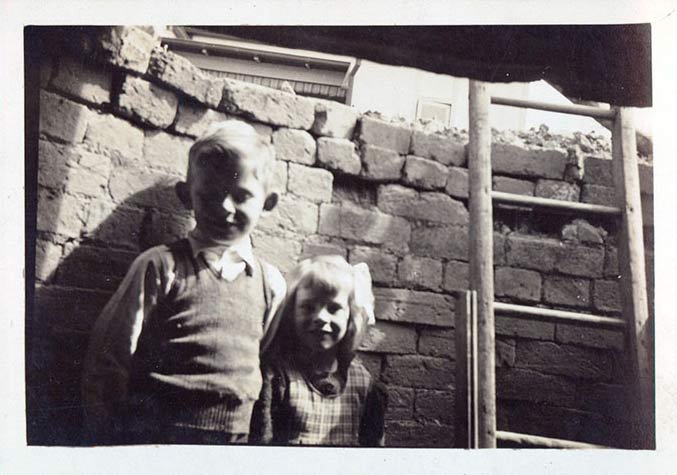

After Dad sailed away to war on the “Queen Mary” in October 1940, Mum, Joan and I moved into Granddad and Grandma’s house in Liverpool Road, Croydon. Uncle Cecil was there as well. It was a narrow house with a high roof as I recall, on a corner block opposite the Western Suburbs Hospital. I remember quite well the little kiosk on the hospital side of Brighton Street and Mr. Pike who ran it. “Pikey” we called him and he was popular with all the local kids because he would always find time to have a game such as pretending that “he had run out” of the ice cream or sweets or whatever else we were buying. Of course he always managed to find the item somewhere! I don’t remember much about the inside of the house except that it was dark even on a sunny day — probably from small windows but also from the dark furnishings. I do recall the round oak dining room table which was always protected by a heavy dark green cloth with a fringe hanging right around the border. I used to enjoy running my finger along the bottom of the fringe to observe the wave like patterns. Although the block was narrow, there was a long back yard with a paling fence at the back and both sides, so there was plenty of space for games and of course plenty of space for us to bring our miniature Pomeranian dog “Toots”. Now “Toots” was very much a family dog. She loved attention of any kind and she wasn’t too particular who gave it to her. As long as she knew them! She didn’t like the baker, iceman or the milkman and simply hated the postman. As she had been badly savaged by a greyhound some time before when we were at Links Avenue Concord she wasn’t too partial about other dogs either! But Uncle Cecil was an instant hit and it wasn’t long before a daily ritual evolved whereby she would drop all other activities to play her part. At around 4.30 in the afternoon she would settle down near the side gate in the paling fence next to Brighton Street. There she would wait and listen. Liverpool Road was a busy road even in those days, so how “Toots” could pick up the sound of Uncle Cecil’s Triumph motor bike from all the other car and motor bike engines when we couldn’t I don’t know. But she could! Suddenly the ears would stick straight up and she would give a little yelp. Then she would jump to her feet and start running up and down the yard next to the fence barking excitedly. Soon we could hear the sound of the motor bike ourselves and sure enough, it was Uncle Cecil home from work! Then it was game time. After he had put the motor bike away Uncle Cecil would come back to the mown area of the back yard where “Toots” would be waiting expectedly crouched down on her haunches. Uncle Cecil would then wave his arms around in exaggerated gestures and yell “Gooooo Tooootsie” and she would race round and round the yard in a big circle as fast as her little legs were able until near the point of complete exhaustion and then she would trot over to Uncle Cecil for a pat and a rub, tongue hanging out and puffing like mad. It was a good game and we all enjoyed it. But further down the back yard was a reminder that it might not always be game time. Next to the trellis covered by a sprawling grape vine was the air raid shelter. In years gone by, a previous owner had constructed a circular well. It was about 8 to 10 feet in diameter and made of bricks. I don’t know how deep it went or how successful it had been, but apparently at some stage it had dried up and been filled in. Granddad, who had been in the Home Guard at some stage during the 1st World War, decided it would make an ideal air raid shelter so he dug it out again over a period of time to a depth of around 12 feet. He had a wooden ladder permanently resting against the wall and he had heavy timber covered with earth over most of the top leaving just enough room to get in and out. |

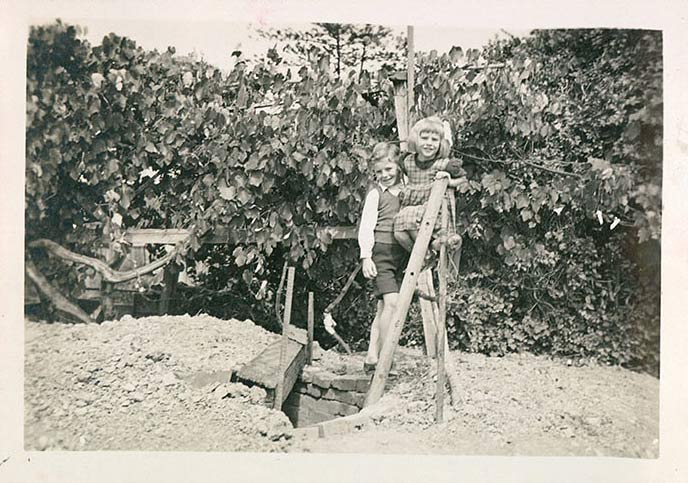

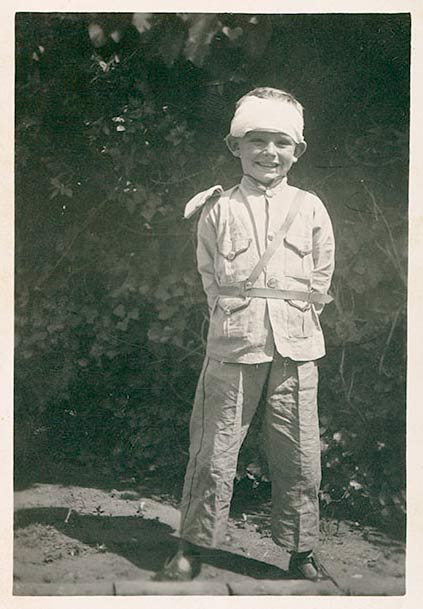

Joan and I were discouraged from playing down there which was a pity because it would have made a great cubby house but I used to pester Granddad into letting us go down there on odd occasions at the weekends when Granddad was working around the back yard cutting the grass or tending the vegetable garden. I was very fortunate that for Christmas 1940 Santa left me some great presents which were very appropriate for the times. A dark green pedal drive armoured car with a ratchet machine gun mounted in a front turret was the ideal vehicle to attack and destroy all those horrible “Germans” fighting my Daddy, and a soldier’s uniform with cap and tin helmet to cope with parades or active duty seemed to my way of thinking just about the ultimate combination. |

The air raid shelter not unnaturally became very much part of the master war game plans I devised and was able to assume the role of enemy stronghold or general headquarters as the case may be —even if I couldn’t go down there. Poor “Toots” became the enemy on many occasions as I would chase her around the yard in the armoured car ‘machine gunning’ her to bits! She seemed to sense she was in some form of danger and certainly didn’t like the ratchet noise of the gun so usually skulked off somewhere with her tail between her legs until I’d ended my game. Joan didn’t like playing my games either much preferring to play with the huge doll that Santa had brought her. It was hard for a soldier to get cooperation! She occasionally would don her nurse’s uniform though and the doll would become a victim of war that she would swathe in bandages. Right down at the bottom of the back yard was an area which wasn’t much used. It was too rough to mow and there were quite a few weeds. I can’t remember why but one day I was running helter skelter down the yard and ran straight into this unused area. Suddenly I was falling headlong — then BANG! My head hit something very hard and there was blood everywhere and blinding pain! Mum held a cloth of some kind to my head and rushed me across the road past Pikey’s kiosk to the casualty section of the hospital where a doctor stitched up a deep cut in a fast rising lump above my left eyebrow. He finished the job by winding a long bandage around my head a few times, just like Joan had bandaged her doll. Granddad then proceeded to dig up the object in the ground that had so nearly penetrated my skull and killed me. He had to dig a huge hole to pull out an old brass bedstead with spear shaped tops that had been buried standing up! I had been very lucky. Needless to say I had my photo taken complete with uniform and tin hat standing near the air raid shelter. It was just like the photograph of my Dad standing near his dugout in the Western Desert. I was a real soldier now, and I had the wound and bandages to prove it! |

Back to page menu | Back to writing menu |

The Radio Rascals The big event of the week for all the kids at Cooma during the war years was the Saturday matinee Picture Show at the Monaro Theatre. It always started with a serial such as Captain Midnight, The Phantom, or The Lone Ranger and the settings would be from such varied places as the Wild West of America, the oceans of the Spanish Main, or the desert sands of Arabia. It always took exactly 12 episodes for the hero to overcome all the gangsters, outlaws or other evil doers as the case may be, and along the way each episode would end with the hero (or heroine) facing certain death — and in the very next episode he (or she) would defy all logical reasoning to somehow extricate themselves in truly amazing fashion. The same old faces would appear from one exotic story to the next (Gilbert Roland was typical) and they were all produced by Sam Katzman and directed by Spencer Bennett and Thomas Carr. Needless to say there was much speculation at school during the week as to how the hero was going to overcome the inevitable, but for all the fertile minds of the self-styled experts, including myself, I cannot recall anyone ever correctly guessing the means of extrication. With so many children attending each Saturday afternoon session, Radio 2XL Cooma (the Voice of the Snowy Mountains), in conjunction with the manager of the Monaro Theatre, Mr. Betts, started a club. The idea was to encourage young talent — singers, musicians etc. to perform live on stage after the movies were finished and if the standard was good enough they would broadcast a half—hour weekly show. One of the radio announcers who took the name of “Uncle Jack” compered proceedings and they were able to get the loan of a good piano and the services of a fine accompanist. The idea took off, and so was born “The Radio Rascals”. At around 9 years of age I was very fortunate to have a pleasant soprano voice. I enjoyed singing at Sunday School, and I had already been involved in some minor solo work for their anniversary. As Dad had done quite a lot of public singing before the war, being involved in such oratorios as Stainer’s “Olivet De Calvary”, Mendelssohn’s “Elijah”, and Handel’s “Messiah”, Mum thought it was a wonderful opportunity to encourage me to follow in his footsteps. She was further encouraged when she heard a broadcast on the ABC recorded on location in Tobruk by the famous war correspondent Chester Wilmot of an army concert compered by Dad and where he sang “‘Til the Lights of London Shine Again”. So Mum chose some songs for me, and although we didn’t have a piano she took me to a neighbour’s house to practice after school, and it wasn’t long before I was up on stage like the rest, singing away in front of the audience and over the air waves of 2XL. Songs I sang included “Christopher Robin” and “Teddy Bear’s Picnic”. I found it fairly daunting at first, but after a while I started to feel more confident and became one of the regular singers. As the year 1944 drew to a close, it was decided to extend the last programme of the year to a full concert where the ten best performers from the previous months would compete against each other. The winners would be decided by voting. One winner would be voted by the theatre audience and the other winner by postal votes from the radio audience. Mum was excited because I was one of the ten chosen. She had seen or heard all the opposition and she was confident I would win. I’m not sure how the order of the programme was decided, perhaps by ballot, but when Mum saw that I was to be second, she began to be more than a little worried. She said that I would have to be at my very best and make a strong impression, because she felt that people would vote more heavily for the items freshest in their minds — near the end. So when my big moment finally arrived, I walked rather nervously out on stage to the biggest audience I had seen. The Monaro Theatre was a sea of faces and as I started to sing “When the Lights of London Shine Again” I endeavoured to focus on as many people as I could see. I could see them looking back at me just as I’m sure the soldiers in the audience of the Tobruk concert had been looking at my Dad. That thought gave me strength and I still remember the words—

As I scanned the different rows I realised that some of the audience were silently mouthing the same words that I was singing, so I was suddenly seized with an inspiration. Just as the piano was leading into the final chorus I spread my arms apart and said “Everybody!” So as the pianist pounded out the reprise of the last three lines, a large part of the audience lustily joined with me for a mighty finish. The applause was sustained and enthusiastic and as I bowed to their smiling faces and walked off stage I knew I had done my very best, and must have a good chance of winning. But the strongly felt sentiment for the ending of the war shifted very dramatically to the last performer of the evening, Janice Norris. Janice was a rather plain, slender girl with straight blond hair from 5th Class of the Catholic School. She had a very clear, pleasant voice and sang very well, but the reason she caught the sympathy of the audience was not because she sang so well or for her choice of song. It was because the compere announced that she was almost totally blind. When the votes came in Janice won both awards and I was second. “There’s always next year, Raymond”, was the popular consoling remark, but the war was over next year and Dad came home, so before there was any thought of another concert we were all back in Sydney, and I wasn’t a “Radio Rascal” any more. Somehow it didn’t worry me! Back to page menu | Back to writing menu |

Lilli Pilli - Story 1 There are really three stories which come to mind when I think of this lovely spot in Port Hacking on the southern side of Sydney, but only one of them occurred exactly at the place which bears this name. When Dad came safely home from the war we all moved back to Sydney, initially to Woronora for a recuperative holiday, and then to Maroubra to stay with Granddad and Grandma. It was from here that I made my first acquaintance with the tranquil waters of Lilli Pilli. I had first tried my hand at some fishing — literally from the front yard at Woronora, where I had caught some mullet and a smallish flathead using a makeshift rod with a short piece of line tied to the end, so when Dad organised a proper fishing outing where we would hire a rowing boat, I was naturally very excited — as any normal 10 year old boy would be. These were the days before nylon lines, and as Dad’s assortment of gut lines wound on corks had been unused during the war years, they were not in the best condition. He had to spend quite a long time carefully preparing his gear on the Friday night before our Saturday outing to make sure that there were no weak links, and Mum gave a demonstration of her patience and good eyesight by untangling some knotty problems. Naturally I was a very wide eyed spectator to all these proceedings. The best time for the bream that we were after was early morning so we made an early start and anchored the boat near a steep shoreline with handsome trees overhanging the placid dark green water. We were using peeled prawns for bait but although Dad said it was the best bait for the wily bream, the fish didn’t seem to agree with him for as the sun climbed higher in the sky, both Mum and Dad had only a couple of small ones in the bag and I had yet to open my account. Of course as the junior member of the party I was using the line made up by knotting together a number of shorter lengths that Mum had resurrected — as I wasn’t expected to catch anything worthwhile. Prompted by a stream of questions, Dad had instructed me on the various habits of the bream and the techniques of catching them. He warned me against striking too soon, and to let the fish run at least five yards with the bait, so armed with all this new found knowledge I was very anxious to put it to the test. The catching of even two small bream had increased my feelings of excitement and expectation. Perhaps too much. As the morning wore on I had found the wooden rowing boat to be much more uncomfortable than I had imagined. The seat was hard, and each time I tried to move to a more comfortable position Mum or Dad would tell me to sit still. They tried to impress on me the necessity for quietness as the bream were very timid. So there I was, ramrod stiff, trying to do the right thing when I managed the unthinkable. I dropped the bailing tin into the bottom of the boat with a dreadful clatter! The sound echoed around Lilli Pilli. “That’s it!” said Dad, looking right at me. “We may as well pack up and go home now. You’ve frightened all the fish away from this spot”. I felt terrible and Mum must have seen how upset I was, particularly when Dad proceeded to pull up the kellicks. “It was only an accident, Cyril, Raymond didn’t mean it, I’m sure. Why don’t we just try another spot? After all, we weren’t doing too well here anyway.” “Please, Dad”, I said, “I’m sorry about the tin, we’ve still got plenty of bait. I promise I won’t make any more noise”. “Oh, all right then, I suppose we could give it a go a bit closer to the boat shed”, Dad conceded. “That way there won’t be as much distance to row back”. I gave a sigh of relief and looked around to Mum to give her a smile of thanks. So we re-kellicked and threw our lines out again with fresh bait. It was a long way down to the bottom — even further than before — and I didn’t have too much line left, so I was wondering what to do if I got a bite, but I decided under the circumstances it was better not to ask any more questions. The minutes ticked away and quietness reigned supreme. All of a sudden I could feel the line being pulled across my finger! With mounting excitement I watched the few remaining coils of my line disappearing from near the empty cork on the bottom of the boat. I couldn’t wait any longer. After two yards maximum I stopped the line with my thumb and pulled. “I’ve got one!” I exclaimed as I could feel the weight of the struggling fish from the depths below. I could see the line cutting through the water first one way then the other as it tried to shake free, and I was aware that the line had cut through the skin of my finger as well. This was no tiddler — it was a big one! I was perilously close to the end of the line tied to the cork and Dad could see the problem. “Quick, let me take it”, he said, grabbing at the line, and virtually pushing me out of the way. “Don’t lose him, Dad. That’s my fish!” I implored, reluctantly but dutifully handing the line over. So Dad attempted to land my fish, but it wasn’t easy and he had to be careful of breaking the ancient line, letting it slip slowly through tensioned fingers as the fish frantically ran with darting thrusts, and then retrieving it gently yard by yard as ground was yielded. He must have been cursing every knot in it! I was looking over the side of the boat, my heart thumping with excitement, when I suddenly saw it! What a magnificent sight. As the beautiful silvery fish turned it caught the noonday sun and flashed like a zigzagging spotlight from the inky depths. Slowly it rose and its struggles grew less. After what seemed ages, but must have in reality been only a few minutes, the bream was finally at the surface and Mum reached out with the landing net to bring it safely on board. It was just as well we had a net because when Dad attempted to lift it out of the net on the bottom of the boat the line broke off right at the hook. It was indeed a lovely example of a silver bream. Its scales, tinged with gold, gleamed in the sunshine. Cleaned, it weighed two and a quarter pounds. A beauty! After all the excitement of catching such a big fish but being denied the opportunity of landing it, I felt cheated somehow, but still pleased nonetheless. The final indignity however, the ultimate let down, came later, when Dad went home via Petersham to give the fish to his father, Papa. I wasn’t able to eat any of it either! …Such was my first experience of serious fishing! Back to page menu | Back to writing menu |

Lilli Pilli - Story 2 Three or four years later when we were living at Normanhurst, there was a period when we regularly made the early Saturday morning excursion to Lilli Pilli to tackle the bream. We would set the alarm for 3.30am so that we would be in time to hire our rowing boat from Boffinger’s Boat Shed when it opened at 5.30! Bob Boffinger himself was quite a character with a very dry sense of humour and a deep gravelly voice. “I must be mad, getting up this early in the morning”, he would say in his heavy drawl, but then he would add, “You fishermen must be worse than me because you’re not getting paid for it!”. We had changed our fishing technique for the bream, finding more regular success with what is termed “long trace fishing”, and instead of prawns for bait we switched to mullet gut and “pudding”. The “pudding” was a mixture of flour, saveloy, cheese and just enough water to make a very stiff dough. To use this different approach we also needed fast running water, so whilst we hired our boat at Lilli Pilli, we usually fished at a place called Rathane on the western side of the Port. It was about a twenty minute row. On this particular Saturday, Mum, Dad and I had all caught some good bream and a bonus for Mum was a very nice tailor of around three pounds. This was a first for any of us so we were all feeling well contented with the way the morning’s events had unfolded. By tea and biscuits time (about 9.30) the count was 12, which was fairly typical for a good morning. We had adopted the practice of keeping the fish alive as long as possible by keeping them in a hessian sugar bag hung over the rear side of the boat and secured by passing small holes cut in the top of the bag over the rowlock. This allowed the fish to swim freely in the water within the bag. Due care had to be given when transferring a freshly caught fish to the bag so that it didn’t miss the opening and slip over the side and we sometimes held it open for each other to avoid this possibility. The weight of the fish stopped the bag from coming loose over the top of the rowlock. Because we were fishing in deep, fast running water it was imperative that we used long ropes to each kellick, so that the angle of the kellick rope was not too steep, and for convenience the ends were tied to each other under the seats, so that the boat’s position could be easily adjusted across the current. All Boffinger’s boats were properly equipped for his regular customers, and all his regular customers knew the correct way of mooring so that the kellicks would hold the weight of the boat without dragging. Unfortunately, some of the members of the power boating fraternity who used the wide expanses of Port Hacking for purposes other than fishing did not appreciate the need for long kellick ropes and many did not have the good manners to give fishermen a wide berth or slow down when passing near them. It was not uncommon therefore, for us to be tossed around by the backwash from boats passing near us on our outside, but we were simply amazed to look around, as we sat drinking our morning tea, to see an approaching runabout, with a huge bow wave, coming between us and the shore! Our first concern was for the kellick rope being caught in the runabout’s propeller, so as we gulped the last of our tea, we tried to wave him away from us, but he kept on coming and passed dangerously close to, but successfully over the rope without fouling it. Then we had to contend with the bow wave and back wash, and as we bounced helplessly up and down like a cork we felt sure that one or both kellicks would drag. And sure enough the outside one did, so we started to swing around with the current, but just as if it looked as though we would have to re-kellick, it held and we breathed a sigh of relief. All it meant was a readjustment of the kellick ropes to pull back a little closer to the shore and we were in much the same position as before but about 20 yards further down current. The unconcerned ‘cowboy’ navigator had meantime taken his craft far away into the distance to upset someone else, so we settled down to take up the fray from near where we had left off. It wasn’t very long before I had caught another bream — a little smaller than average — but as I turned around to put it into the bag I couldn’t see the bag in its usual place. Puzzled, I looked around the boat and asked, “Where’s the bag?”. Mum and Dad looked around not quite sure what I was referring to, but almost simultaneously as we surveyed an empty rowlock, the penny dropped for all of us. The bag of fish was gone! The bouncing of our boat when the other one came so close had lifted the bag clear of the rowlock and the bag and fish had then disappeared into the depths. Our spirits sank almost as deeply — Mum’s especially, as it was her big tailor that was gone. “Well, that’s that”, pronounced Dad. “All we can do is to start again. One thing for sure, I will never again hang a bag on a rowlock like that. That’s one lesson I’ve learnt today”. So we continued on, trying to add to the last one that I’d caught, but the best part of the tide and the morning had just about gone and there weren’t too many bites. Progress was slow. It had been a fairly cool, cloudy morning up to now, but as we contemplated the change in our fortune the clouds started to disperse and the sun made a warm appearance. The water beneath us was around 30 feet deep and the bottom was sandy. As we fished I noticed Mum looking over the side peering into the water first at the front and then the back. “It’s no good looking for the bag, Evelyn, it could be anywhere by now”, said Dad. “Anyway, the fish would have found their way out long ago”. “There’s no harm in looking”, Mum replied. “I haven’t got anything better to do”. Mum had apparently lost all interest in the fishing. “Well, try these and maybe you’ll be able to see a little better”, he said dubiously, passing her an old pair of Polaroid sunglasses he found from his fishing basket. So Mum went on looking using the sunglasses, and after a while she declared from the back of the boat, “I think I can see the bag. Cyril, rig me your strongest line with a large hook and a heavy sinker. I’m going to try to hook it”. With the glare on top of the water, Dad and I couldn’t see anything very much at all. I thought I could see a small dark shape but felt it was probably a rock. Dad knew better than to argue so he duly complied, muttering that it was all a waste of time, but Mum was soon casting out and drawing in slowly with a very determined look on her face. After only a few minutes she announced triumphantly, “I’ve got it!” Both Dad and I watched with quickening interest as hand over hand Mum proceeded to pull in a heavy load of some kind. We were surprised to see that it was indeed the missing bag that was rising to the surface but simply astonished when Dad lifted it dripping wet into the boat and found all the fish still in there! Mum was ecstatic! She had hooked the hessian about six inches from the top, so that when it was lifted clear of the sand the bag had folded over! If the bag had been hooked near’ the bottom all the fish would have been tipped out! Needless to say we were all very impressed with Mum’s efforts. When we returned to the boat shed and told Bob Boffinger about it he drawled with a sly grin, “I thought you were going to tell me that some of their mates had swum into the bag to keep them company!” Back to page menu | Back to writing menu |

Lilli Pilli - Story 3 Shortly before leaving Normanhurst to go to New Zealand, Dad took me fishing to Lilli Pilli for the last time. We were now chasing the more intrepid blackfish; a fish to test the skills of any angler — hard to catch and even harder to land! Fishing techniques are entirely different for this species as they are mainly vegetarian, requiring a long, moss type green weed for bait, and it is essential to use a rod and reel of specific types. Through trial and error, and by learning from others, we had gradually acquired efficient outfits and mastered the methods of using them, to tackle this intriguing quarry with some considerable success. The one common factor between bream and blackfish is their habitat which is quite similar, and the best way to reach their habitats in Port Hacking was by boat, so once again we headed for Boffinger’s. The day started peacefully with clear skies and light breezes. Dad had decided to fish the run out tide near Rathane where nearly a couple of years previously, Mum had miraculously retrieved the lost bag of fish. Since that time we had been using a keeper net made of strong twine netting, held together at the top by a loop of cord through a series of brass rings bound at equal distances around the net opening. We then tied the loop to a fixture on the boat. No chance of any accidents! Unfortunately, after the first hour or so of this particular morning we had been unable to put it to good use, as there had been very little interest shown in the baits we offered. We felt this was probably due to the large amount of ribbon weed in the water, which not only made fishing quite tricky, but in addition had gradually collected in large masses along the kellick ropes, until eventually the extra weight had proved too much for the the outer kellick, and we started to drag. As we attempted to re-kellick we realised that the tide was unusually strong and Dad had great difficulty in rowing the boat into the correct position. After a great deal of effort, and I might say quite a deal of skill, by using most of the available rope, we managed to moor the boat successfully and started to fish again. The tide was fairly racing by this time and was taking our floats away from the boat to the point where they literally disappeared from sight in a matter of seconds. We also became aware that the light had changed dramatically, as the carefree, blue sky had been replaced by dark, sinister clouds and a strong wind had arrived to whip up the surface of the water. It looked as though we were in for a storm! In normal circumstances we didn’t mind fishing in the rain as we each had weatherproof jackets, but the wind was coming from the southeast and was blowing directly across our drift. With this added to the weed problems and the big tide, the equation came out in favour of a unanimous decision to move to a more protected spot — as quickly as possible. This proved much easier said than done, but by the time the rain had started to beat down on us, we had shaken off all the weed that had once again collected on the kellick ropes and with considerable difficulty, lifted the kellicks on board. We had decided to head for “the Hole” at Lilli Pilli. This was a popular spot with very little run and it was well protected from the south-easterlies. It was normally a twenty minute row. Dad started rowing, but it was soon obvious that heading into the wind and across the current we were going to make slow progress. After ten minutes Dad had to have a spell. I took over and soon found how tough it was. At least I had my back to the rain which by this time was really lashing down. The waves were now up to three feet high and as the bow crashed into each wave it sent spray flying everywhere. I had to continually pull more on the left oar because the current was trying to force the boat away from where we wanted to go. Soon it was time for Dad to take over again, and it was a tricky manoeuvre changing seats in the bouncing boat without falling overboard on the one hand, and trying not to lose too much progress on the other. It was accomplished by staying as low down in the boat as possible. It was also imperative that we maintained the heading of the boat into the wind, because if we turned sideways there was a real danger that we would capsize. This became even more important as we started to negotiate the shallower water over the sand flats out in the middle because it was here that the effect of the wind was greater and the waves were higher and rougher. We had swapped positions a number of times as it was very tiring work. Dad was rowing in the worst section when disaster struck. The left oar broke at the rowlock! The handle stayed in his hand but the blade section dropped into the water. As it slid down the outside of the boat I reached over and grabbed it just before it was lost. The boat started to swing around and we were bobbing up and down in a very uncomfortable fashion. Dad was yelling instructions and desperately trying to control the boat with one oar. Somehow with all the tossing I managed to get the broken and now considerably shortened oar back into the rowlock for him. Because it now slid easily in the rowlock without the rubber holder it was almost impossible to control, but he managed to turn the boat into the wind again and avoid any capsize for which I was grateful because there were no life jackets and I was not a strong swimmer. With this new development there was now no thought of trying to reach Lilli Pilli. “We’ll head for shore as best we can and wait until the tide turns”, Dad yelled. So gradually, as the tide took us further and further away from Lilli Pilli, we worked our way slowly to shore. As we moved closer to the protection of the eastern shore the wind and rain slackened and made things much easier. Dad had been forced to take a long stint with the oars and now I was able to give him a well earned rest. We finally stepped ashore in Burraneer Bay, nearly a mile from where we had wanted to go. It was well over an hour since we had started out. Dad was exhausted, and I wasn’t much better. It was time for an early lunch and a cup of tea. The tide would not be changing for at least two hours. After lunch we both felt much better. The storm had blown away, although the wind was still blowing quite strongly out in the middle, as we could see plenty of white horses. With nothing better to do I started to explore our immediate surroundings. There were a number of fine houses nearby but well back from, and high above the water. The hillside was fairly steep and the shoreline rocky. Some of the houses had swimming enclosures built onto the shore of the bay, but no one was using them. Indeed the whole area seemed deserted. As I walked near the edge of one enclosure my eyes nearly popped out, because swimming inside was a large school of blackfish and amongst them were some whoppers. They seemed in magnificent condition and their stomachs were bulging — perhaps with milt or roe. The steel railings of the enclosure were designed to keep out the sharks and maybe that’s why the blackfish felt quite safe to come in. Dad wasn’t too keen on my proposal to get my gear and see if I could catch one. Apart from the fact it was a private enclosure, he had heard, and always believed, that it was impossible to catch blackfish if you could see them. Here the water was so clear that we could easily count the vertical stripes along their sides. I was keen to prove or disprove the theory, so with another look up the hill to see if anyone was coming, I returned to the boat to get my gear and some bait. I cast out gently and watched, fascinated, as my float and bait drifted slowly amongst the school. I remained as still as I could be, not wanting to frighten them. At first there was no reaction whatever to the bait then quite a large one made a definite move towards it and seemed to take it in its mouth. The float hadn’t moved but after a few seconds started going down so I struck. The other fish scattered as I played it struggling to the surface where Dad netted it for me. It was a good fish, about one and a half pounds. After a couple of minutes the school had reassembled in roughly the same positions as before. This was all too much for Dad, and he went back to the boat for his gear as well. We caught five more nice fish in the next half hour and were having a great time particularly after the harrowing events of the morning. It was a marvellous opportunity to observe that which previously we had only imagined. We had failed to tempt the really big ones which we estimated were over three pounds, even though we had literally drifted our baits right past their noses. We reckoned it would be just a matter of time though, and we were starting to experiment with different sized baits by varying the lengths of the green weed when suddenly from about five yards behind us a voice barked, “What the hell do you think you’re doing?” I nearly dropped my rod, and I think Dad must have had a fright as well. It was the owner, and he wasn’t amused, even though Dad did his best to explain what had happened to us. We had to pack up and go — leaving that lovely school of blackfish to somebody else. So we went back to the boat and waited for the run in tide. It was a long and awkward row back to Lilli Pilli, but we had six good fish in the keeper net and the satisfaction of disproving a popular theory. I’ve sometimes wondered whether the owner of that swimming enclosure was a blackfisherman! Back to page menu | Back to writing menu |

| Prev |